A comparison between Reading in the Dark (Seamus Deane, 1996) and The Secret Scripture (Sebastian Barry, 2008)

|

| The individual, society and Nature. BCN |

I missed you terribly, you my sweet little bloggie :) I've been busy with exams; fortunately, the process was over yesterday, from 8am to 7pm jailed in the examination building. Disgusting, humiliating experience. Maybe I should blog about it on its own post, because I do not want to tarnish my gorgeous Secret Reading with ugly thoughts. External circumstances, as always: the exams were rather easy but, as always, the civil servants are a shame to society... because they are society. In any case, Sebastian Barry, I missed you terribly too. I have to kindly thank you for taking my circumstances into account and not having sent your signal for me to start On Canaan's Side yet (I take special pride in consuming my favorite artists' latest work some months after their publication... patience always pays off :)). So this is the continuation of The Secret Reading I had to split in two in the previous post. Let's briefly remember where we were at. I ended the post with a quote by Barry's Roseanne in which she deconstructs the binary society/individual. I think –I interpret those lines as that– an individual always has the last word when in a battle against society; the individual always wins, at least morally, that's what matters. Now we are ready to go back to The Secret Reading...

Another common ground the main characters of Reading in the Dark and The Secret Scripture share as narrators is that they are outsiders. For one reason or other (remember that my blog is spoiler-free...wink-wink!), they are in the margins of society. Roseanne's marginalisation is progressive, or rather, intermittent; Deane's is probably inherent since he is born, living in a foreign country, in occupied territory with discriminatory tendencies towards the Irish:

|

| DERRY. April 2012 |

“This was border country (...) Even when no one could be seen, we felt we were being watched”(...) At the other end, the Free State began (D: 49)

But politics and history aside, he also feels displaced from within his own private sphere, his family. Both internal and external marginal forces intervene when society sees his family as a “marked”one (D:27). Both authors seem to illustrate in their respective novels that “[p]eople in small places make big mistakes. Not bigger than the mistakes of other people. But that there is less room for big mistakes in small places.” (D:212). All this factors stimulate Deane's quest for identity, first to collect all the jigsaw pieces, then to put them together. In my opinion, one of the most delicious features of both novels is the love of nature. The celebration of Mother Nature as the rejection of religion. More clearly in Deane's, but Roseanne –in spite of her strong faith in a Christian God– is no less devoted to Goddess Earth; she summarises paganism is these lines:

“The human animal began as a mere wriggling thing in the ancient seas, struggling out onto land with many regrets. That is what brings us so full of longing to the sea.” (B:144)

|

| The Giant's Causeway... Finn McCool, the Fianna and the Grianan. |

The sea is life-giving. The fetus in its mother's womb is like a fish in the sea. There is an innate, an ancient –to use Barry's adjective– connection of human beings to the sea. Additionally, a 75%-80% of our body is made of water. Water calls for water. Nature is female because it gives birth to beings. Her blood is the water. This fertility is found in female human beings and birth-giving involves fluids, the fetus in the womb. Barry is a sublime feminist. Okay, I have to be careful with this word. It is so annoyingly relative! Depending on the era you are talking about or from, it can mean one thing or another. I mean feminist in the sense that he analyses, and ultimately condenms, society as a construct made by man for man in which women are subjected to the whims of man. There is no clearer example than Roseanne's case. To further sustain my argument, her heroine is referred in the novel as “a force of nature”(B:17). As far as Deane is concerned, his intense bound with Nature is brought forward by the Grianan. “[T]he sleeping warriors of the legendary Fianna”, waiting to be called upon. And look here, another exciting implication. The Fianna are buried in green Irish soil, they are Éire, the ancient Celtic nation, they are Nature, they are Ireland. Same as Barry, Deane takes us back to pre-civilization, to something more primitive, more ancient, wiser... Nature. THE SEA. Notice that Deane also treats 'woman' and 'water' as synonyms!

|

| Mosaic @ Garden of Remembrance DUBLIN |

"When I shouted, my voice ricocheted all around me and then vanished. I had never known such blackness. I could hear the wind, or maybe it was the far-off sea. That was the breathing Fianna. I could smell the heather and the gorse tinting the air, that was the Druid spells. I could hear the underground waters whispering; that was the women sighing".(D:57)

|

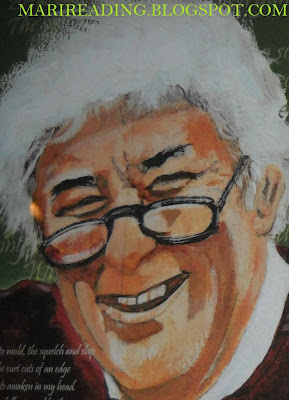

| Seamus Heaney @ Temple Bar, DUBLIN. |

Deane's mother is described in the novel as having “a touch of the other world about her” and also let me tell you that Deane is another marvelous feminist. In the chapter that gives name to the novel, “Reading in the Dark”(19), the narrator reveals that the first novel he ever read was a book from her mother called “The Shan Van Vocht, a phonetic rendering of an Irish phrase meaning The Poor Old Woman, a traditional name for Ireland” (D:19). As you can see, the comparison between Nature and Woman expands and we have a triangle thanks to the Ireland implication; traditionally, all the greatest poets have developed the image of Ireland as a woman. Even Seamus Heaney keeps drawing on this tradition, in his poem“Act of Union”, describing this union with Great Britain as a forced marriage, etc. I love the implications that Deane arouses here, listen: in her mother's book, the son finds his mother's maiden name handwritten there. His reaction is the following: "They seemed strange to me, as though they represented someone she was before she was the mother I knew" (D:19). This intense triangle awakens all the more interesting ideas in my head, like the notion that probably Deane's mother can be read/works as a symbol of Ireland.The exploitation and violation of Ireland by the British governments and forces as the ill-treating of woman by the patriarchal society expected of officially Catholic Ireland. The Emerald Isle, Éire, the virgin green soil, Mother Ireland, Mother Earth, Goddess Earth. The Poor Old Woman, after the forced marriage with the British tyrant (“And I am still imperially / Male, leaving you with pain” S. Heaney). Deane's mother's maiden name, pre-society. See? An Irish woman of her times was a double victim: of Irish history, and of British too. A sublime novel never wears out. It never wears you out either. Never exhausted, always new things to learn and explore! To sum this paragraph up, Deane and Barry are amazing feminists, to achieve that they turn to Nature. Out of civilization. Out of religion. Out of politics.

|

| Reflections: Garden of Remembrance, DUBLIN. |

To end this list of features that Deane's Reading in the Dark and Barry's The Secret Scripture share, let me add a shallow one: the front covers of my copies. They are the ones in the picture I posted in the previous post. Misty mysterious emotions were aroused when I first laid my hands on them. Reading in the Dark: the old worn-out picture in a broken-glass frame speaks directly to you. About broken families? About conflicted childhoods? Cracking Ireland? If the first time you see the cover you know that Seamus Deane is from Derry and was a direct witness of The Troubles, the image of the broken glass will awaken even more implications. As if all that shallow beauty wasn't enough, on the back-cover we have some lines by Seamus Heaney himself, another Derry-man. According to him, the novel is “(...)a swift, masterful transformation of family griefs and political violence into something at once rhapsodic and heartbreaking”. These lines confirm your initial suspicions as regards your novel expectations based on the book´s outward design. Nevertheless, you could never do justice to this novel in words, not even a Nobel Prize like Mr Heaney himself :) You've got to feel it. As regards the cover of The Secret Scripture, since I hate repeating myself, I will kindly redirect you towards a previous post in which you can read me talk about its overwhelming beauty.

|

| Union Jacks clouding the Irish sky... (BELFAST, Sept 2011) |

Having

reviewed all the points in common, it is time to draw the portrait of

each author individually. I have to confess that despite the long

list of similarities, their profiles as Irish authors of fiction

could not be more disparate. Despite the generalizations I have

previously discussed, and the labels I have created to draw Deane and

Barry together, each of them is unique in his own way. With such

charismatic similarities, the differences, as you can imagine, are

abysmal. Deane, as the dedicated literary critic he is, gives top

priority to form. For Barry, as the crafty creator of delicate,

stimulating and often problematic narratives that he is, plot takes

precedence. Unfortunately, I think The Secret Scripture,

as far as formalistic devices is concerned, is not very original,

nor successful. Maybe if I had read it in isolation, without having

read Deane's novel first, I would have not paid much attention to

this aspect, as usual. To tell you the truth, I'm more of a lover of

content than of form! Nevertheless, I have to excuse Mr Barry for

that :) Maybe I am getting biased towards him since he is haunting me since Dublin, you know :) but a tale of the proportions of The

Secret Scripture is difficult to

contain in a kind of narrative other than the diary form. I think the

author took his time and dedication to decide why this form and not

another. I suspect Barry must have thought that the content had such

an intense life of its own that if he paid too much attention to form

originality, the content might lose gorgeous weight or, eventually,

crumble. In sum, Roseanne

had to speak to the

reader directly:

“Dear reader! Dear reader, if you are gentle and good, I wish I could clasp your hand. I wish – all manner of impossible things. Although I do not have you, I have other things. There are moments when I am pierced through by an inexplicable joy, as if, in having nothing, I have the world” (B 24)

|

| DALKEY, Dublin. |

Imagine

The Secret Scripture

in a Reading in the Dark

form. Very risky. Besides, we have to bear in mind that, arguably,

Barry's goal was to re-write Roseanne:

"We were driving through Sligo, and my mother pointed out a hut and told me that was where my great uncle's first wife had lived before being put into a lunatic asylum by the family. She knew nothing more, except that she was beautiful. I once heard my grandfather say that she was no good. That's what survives and the rumours of her beauty. She was nameless, fateless, unknown. I felt I was almost duty-bound as a novelist to reclaim her and, indeed, remake her." (Interview: The Guardian)

|

| Ballintoy, Northern Ireland. |

I

love this explanation. Barry's project is to set Roseanne's

micro-narrative against the backdrop of the Irish metanarrative of

the 1920s and 1930s. The structure of his novel reminded me of Bram Stoker's Dracula. It

is very similar, same style: juxtaposation of diaries. Obviously the

final product tastes a bit artificial. I would say that in Dracula

it gets more real, it is more reasonable. Nonetheless you cannot

escape from that synthetic flavour. But in The Secret

Scripture, the form lacks

freshness, it is too traditional. In any case, the author must have

chosen the journal form to present Roseanne's

story without filters. Besides, it was the only way of

presenting the conclusion of the story, when all ends meet. A bit

Dickensian, isn't it? But life is like that, I bear witness!

Approaching

Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark formalistically,

I have to take my hat off, to

solemnly bow, to kneel down

before him. It is fresh. So minimalistic but meaningful. So

straightforward. Every chapter takes the name of a word or a phrase

that condensates its mood or theme. Some of the chapters are so

short... I suspect that's a sweet little trick from Deane to get us

totally hooked on the novel. As a matter of fact, it is necessary

that he irremediably creates the atmosphere for our textual desire on

him... his novel is full of gaps –remember those gaps we discussed

in a previous post? The novel works by insinuations, impressions,

hunches, impulses, suspicions, premonitions... the non-spoken rather

than what it is actually said. It is no coincidence that the novel

opens with the following sentence:

“On the stairs, there was a clear, plain silence.” (D:5)

|

| Bloody Sunday Memorial, DERRY. |

Because

of that, it is important to be constant in your reading. It is a very

short novel with very short chapters. It is better to read it in a

week. So you can remember all the little details of the beginning at

the end. Also, because there is a lot

of guesswork expected from the reader. But everything is very well

summarized at the end, just in case. I have the feeling that Mr Deane

is more of a reader than of a writer and that's why he took so much

dedication to dream up that particular form for his novel, for the

story of his life. The short titles and chapters also allow him to

jump forward and skip years. We all have years in which nothing

really happens. That's realism. The novel's peculiar form is a

triumph because you do not notice the span of months or years in

between chapter and chapter as something detrimental to the reading,

to its understanding. On the contrary, it gives dynamism, it keeps it

flowing, despite of the gaps in years. To tell the truth, the

structure of the novel is very simple, but a supreme victory. Also,

his supreme gift for words melts you. Again, very simple style but

able to take you just anywhere. In spite of all the violence, family

secrets and other dramas, our narrator filters the reality with

dreamy eyes. The mentions and descriptions of the Grianan

are remarkably beautiful for instance. Reading in the Dark

is an excellent novel: the victorious form is accompanied by a

beautiful-but-sad plot that makes you close the book with a deep

sigh, yearning for more. (Then it is when you decided to initiate The

Secret Scripture and you have

not stopped sighing ever since :)) Before the end, just let me add:

more points in common, although weaker, see “rats” and the

bombing of Belfast during WWII.

|

| Garden of Remembrance, DUBLIN. |

This post is an adaptation of an e-mail I once wrote for the lovely

person who gave me these two books as Christmas gifts. I have let it

flow, so, obviously, the thing has overflown again, which

means there will be more Deane and Barry posts –this time,

separately– but maybe in the coming months, not next week or the

following. Wow, it it unbelievable that despite the length of this

post I got the feeling I have talked about each novel quite

superficially. See, that is why I admire Deane so much, he has the

divine quality of saying so much in so little space. So poetic (note

to myself: check out his poetry!).This blog is not just about

literature. But I admit that is the subject I write best about. So it

is time to practice and develop other fields! As a matter of fact,

even if this is a literary post, it talks about life, as you have

seen. Life is literature; literature is life.

“The world begins anew with every birth, my father used to say. He forgot to say, with every death, it ends.”

(Opening lines from Sebastian Barry's The Secret Scripture)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- BARRY, Sebastian. The Secret Scripture. London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2009

- DEANE, Seamus. Reading in the Dark. London: Vintage UK, Random House, 1997.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------